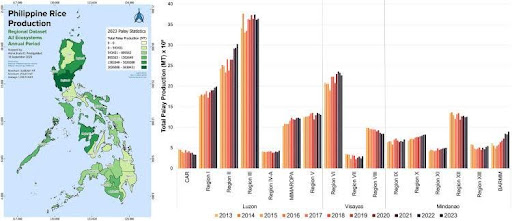

Regional differences in total production of unmilled rice in the Philippines from 2013 to 2023, based on PSA data. Source: Bartelet et al, 2025

MANILA, PHILIPPINES [TAC] – Filipinos were eating 2.3 million metric tons more rice than the country produced—an 18 percent shortfall that has locked the Philippines into deeper dependence on imported rice despite years of government programs to boost local harvests.

In a study by the Ateneo de Manila University’s John Gokongwei School of Management and Department of Environmental Science, citing data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), they found that national rice output has been largely stagnant since 2017.

In ten years since 2013, total production of palay (unmilled rice) grew just 9 percent, from 18.4 to 20.1 million metric tons, even as rice consumption and the population itself continued to rise. Rice farmland barely expanded, increasing by just 1 percent (from 4.7 to 4.8 million hectares), while average yields improved by only 7 percent, from 3.9 to 4.2 metric tons per hectare.

In addition, the researchers did not find strong link between city expansion and overall palay output stagnation. Instead, they point to a combination of limited farmland expansion, slow yield growth, climate shocks, and uneven public investment in rice areas as the main constraints on domestic production.

This is borne out by sharp regional contrasts that emerged from the data. From 2018 to 2023, the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) and Eastern Visayas (Region VIII) saw rice production decline by 15 percent and 11 percent, respectively, largely due to rice farmland loss; stagnant yields; repeated typhoons and droughts; and competition as farmers divert land use to other, more profitable crops.

On the other hand, the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) increased its rice output by 40 percent, while Cagayan Valley (Region II) and Ilocos (Region I) posted gains of 27 percent and 16 percent, respectively. These gains are linked to expanding irrigated areas, better yields, and support programs such as improved seed, farm mechanization, and targeted regional initiatives.

Moreover, seed programs to help ensure robust crops and mechanization aid towards improving rice harvesting and processing have helped boost yield, while infrastructure expansion and regional government policies have helped with farmland expansion.

In the case of BARMM, increased rice yields are linked to dedicated investments in rice infrastructure on top of peace dividends in the wake of improved political stability in the region.

Despite the establishment and subsequent extension until 2031 of the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund under the Rice Tariffication Law (RA 11203), the authors note that national programs alone have not been enough to lift productivity in lagging regions.

Nonetheless, the researchers expressed optimism that, with the right complement of policies and investments, local rice production can still grow and help narrow the country’s dependence on imported grain.

Closing the country’s growing rice deficit will require regionally tailored, climate-resilient strategies: stronger irrigation systems, better-targeted support services, and financial measures that lower farmers’ costs, according to the researchers.